Local History

- Books and Trails For Sale

The books and leaflets can be purchased from the Diseworth Heritage Centre

Email: or Call: 07891 628 292

Diseworth - The Story of a Village

This book details the history of the village of Diseworth throughout the centuries, including its associations with nearby Langley Priory from the early middle ages onwards, and with Christ's College, Cambridge between 1506 and 1920. Well illustrated and with details of life and significant changes during the past century.

Cost: £8.00

Long Whatton - Memories of Times Past

This book covers the history of Long Whatton over many centuries and is full of anecdotes about its inhabitants and their activities. Well illustrated.

Cost: £8.00

Diseworth Parish Church - One Thousand Years of History

This book covers the long history of the Parish Church, including details of the building, its monuments and fittings, the vicarage, activities of the churchwardens, and brief biographies of most of its vicars. Copiously illustrated. Produced as part of our HLF 'All Our Stories' project.

Cost: £5.00

The Baptist Church in Diseworth

This well-illustrated book tells the story of the founding and growth of the Baptist movement in this area leading to the building of the Baptist Church in Diseworth in 1752. It also covers its many activities and challenges since. That building survives today, despite having been badly flooded in 2000, as the Diseworth Heritage Centre.

Cost: £5.00

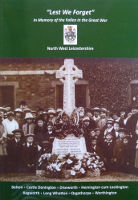

"Lest We Forget" - In Memory of the Fallen of the Great War

This, the second of a projected six volumes detailing the background, service history, manner and place of death, and, site of commemoration of all those service men from North West Leicestershire who died as a result of their service in the Great War of 1914 - 1918, covers the villages of Belton, Castle Donington, Diseworth, Hemington cum Lockington, Kegworth, Long Whatton, Osgathorpe and Worthington.

Cost: £8.00

Diseworth Church Trail

The history of St Michael and All Angels over the thousand years of its existence, complete with photographs and time-line. Produced as part of our HLF 'All Our Stories' project.

Cost: £1.50

Diseworth Heritage Trail

A self-guided trail around the historic village of Diseworth in NW Leicestershire. Illustrated with photographs and drawings by residents.

Cost: £1.50

Long Whatton - a mile from east to west. A Village Trail

A self-guided tour of the village of Long Whatton in NW Leicestershire which contains many very interesting historical properties. As the title suggests, it is well-named - an early example of 'ribbon development'.

Cost: £1.50

- Diseworth Village History

Archaeological evidence shows that the site of Diseworth was inhabited in the Roman, Saxon and Viking periods. Its position in a sheltered valley next to the brook is a classic setting for early settlement, and the development of farmsteads. Diseworth has had many variations on its name, but almost always with the suffix worth, meaning enclosed settlement. The naming of the principal roads (Lady Gate, Hall Gate, Clements Gate and Grimes Gate) also shows their origins in Viking times.

At the time of the Norman conquest, Diseworth was sufficiently important to be part of an award to a Norman knight, and appear in the Domesday book. William Lovett held some 360 acres in Diseworth, although his tenure did not last for long.

By the early 12th century, land around Diseworth was held by the Earls of Leicester and Chester, and by Robert de Ferrers. Many disputes over the ownership of the land followed in the period up to the late 15th century, when in 1487 the estate was declared the property of Sir Henry Colet.

The nearby Langley Priory had exercised considerable control over the parish church and the villagers, many of whom worked for the nuns. Benefactors who donated land to the Priory often chose land in Diseworth. Shortly before the dissolution of the Priory, along with other religious properties and land in England, Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII, purchased a considerable part of the village to found what became Christ's College, Cambridge.

For the next five hundred years Diseworth was dominated by the owners of Langley Priory estate and Christ's College, and saw the villagers paying rent to either the Reverend Gentlemen of Christ's, or the new owners of Langley: first the Grays, then the Cheslyns and then the Shakepears. The college sold their interest in Diseworth in 1920, but there remain a few farms and houses still owned by landlords.

Today, Diseworth is still notable for having several active farms contained within the village itself, although its proximity to East Midlands Airport is a constant reminder that its future prosperity is also dependent on the trade generated by its position in the M1 corridor, close to Derby, Nottingham and Leicester.

Ridge and Furrow today

Ridge and Furrow today

Ploughing Match

Ploughing Match

East Midlands Airport

East Midlands Airport

- Diseworth Baptist Chapel

The Chapel in the 1800's

The Chapel in the 1800's

The Chapel in 1938

The Chapel in 1938

The restored Chapel in 2009

The restored Chapel in 2009

The history of Diseworth Baptist Chapel records the enthusiasm and fervour of very many village people. The Baptist Chapel has been established in the village for over 250 years, and in spite of religious persecution and theological controversy on a national level at its commencement, has offered evangelical witness since that time.

As the evangelical revival which led to the creation of the Baptist Church in England and Wales in the early 1700's was not without controversy and religious persecution, this resulted in very few public meetings and the 'dissenting minsters' as they were called held their early meetings in the weaver's shop, now known as Lilly's Cottage. There was so much opposition that their employers could dismiss workers if it was discovered that they were attending the preaching of dissenters. However, slowly and surely the enthusiasm for the principles of the Baptist Church grew and in August 1751 at the Assizes in Leicester the preachers sought and obtained the protection of the law under the 'Act of Toleration' and preachers were registered as Dissenting Ministers. Shortly after, the small but keen group of followers in Diseworth took the decision to build their own meeting-house. Land and accommodation was found and Diseworth Baptist Chapel was erected in 1752.

Subsequent generations continued the Baptist tradition in Diseworth, until the flooding of the Chapel in November 2000 finally made the building unsuitable for worship. Diseworth Heritage Trust then started campaigning to purchase the building and convert it into a Heritage Centre, and this dream has now been realised with the opening in 2009.

- Diseworth Parish Church

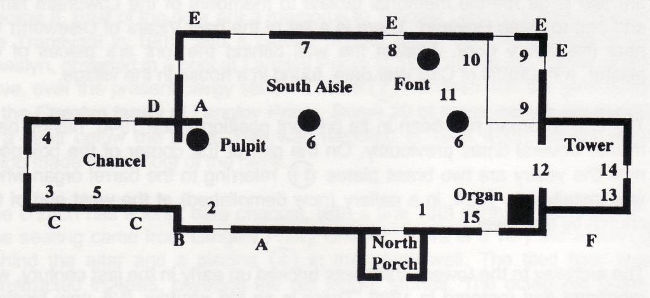

Diseworth Parish Church, which is dedicated to St. Michael and All Angels, stands at 'The Cross', where the four 'Gates' of Diseworth (Hall Gate, Lady Gate, Grimes Gate and Clements Gate) meet. The Village War Memorial is set into the church-yard wall beside the church gates.

Exterior features

The church is built of local stone, predominantly in the transitional or Early English style, with a broach spire. The oldest parts of the fabric, the remains of a Saxon single-cell church, can be seen in the north wall. There are traces of herringbone walling (A) at foundation level on the nave wall and Saxon long-and-short work, quoins, on the NE angle of the nave. (B) The two blocked windows in the chancel (C) are of Saxo-Norman type. Herringbone work can also be seen inside the building at the base of the old external nave wall in the south aisle chapel.

Near the corner of the chancel and the south aisle is a blocked 'lowside' or 'leper' window. (D) Through it, lepers, or the sick in times of plague, could see the altar and take part in the service without entering the church. The south aisle is primarily 13th century work. Its stonework is not tied in to the main building but is simply butted up against the existing walls, with buttresses for stability. The original pent roof line can be seen in the east and west walls. On the parapet of the south wall and near the top of the west wall (E) are four heads, much defaced by weathering. The E and SW windows in this aisle are early 13th century. The taller window on the S wall, which cuts through the original roof line, is early 14th century, showing the date by which the roof was raised and pitched. The south doorway is 13th century and much weathered.

The tower and spire may date from the 1300s. The tower has four triple-chamfered bell openings, their tracery and cusping now removed. The spire has tall broaches and one tier of lucarnes (dormers). There is a ring of six bells. The external west door under the tower was blocked and a new window created when the tower and spire were restored in 1896. The building was originally thatched. The roof was leaded in about 1699. The increased weight led to distortion of the chancel arch so the brick buttress on the north wall was built. Some of the sheets of 1699 lead have markings of shoe outlines, made with a sharp tool. Much of the stone coping from the parapet of the north wall is missing. The church is entered through the north porch which was built in 1661. However, the outer arch is in the same style as that of the north and south doors, and may be made from reused stone as it is very heavily weathered.

- War Memorial

The Dedication, 1921

The Dedication, 1921

The Memorial in November 2007

The Memorial in November 2007

Researching the names on the War Memorial

This research started in a chance conversation with Barry Smith between Christmas and New Year 2005/06. Barry mentioned that the Vicar had commented on the large number of names on the Diseworth memorial relative to the size of the village. This started him thinking about whether the names that were commemorated each year on Remembrance Sunday were correct and he started checking. Did some of them return? Barry also told me that there was a mystery about a grave in the churchyard for a John Allcroft, as nobody knew why he was buried here. This is the story of what we found.

This is the full memorial:

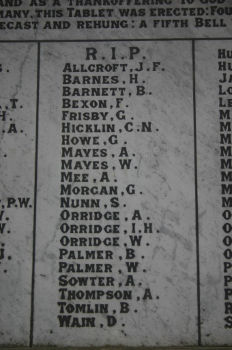

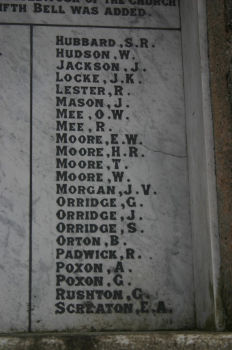

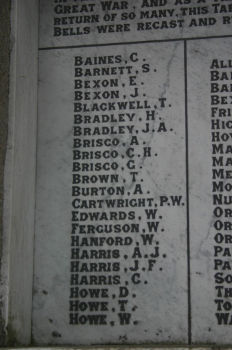

This is the central panel headed 'RIP' which we assumed contains the names of those who did not return:

These are the names on the two side panels who we assume did return:

I needed to check from original sources whether the men on our Memorial centre panel died in the First World War. I also wanted to check that the men were local, by seeing if I could find them in the 1901 census for the village, as most of them should have been born by then. To do this I looked at websites for:

- The Commonwealth War Graves Commission at cwgc.org.

- The Royal British Legion at roll-of-honour.com/Databases.

- BBC Radio Leicester website for those in the Leicestershire Regiment at bbc.co.uk/leicester.

- 1901 census online to search for 'village names' at findmypast.co.uk.

To try to find the graves of others on the Memorial who had more common names, I also looked at the Radio Leicester website to try to find our men and also at the British Legion website connected with the Leicestershire Regiment, although of course not all were in this regiment. Through these various websites I managed to find war graves for the following names on the Memorial, although in some cases I remain unsure if I have found the correct person:

- John Allcroft

- Harry Barnes

- Bernard Barnett

- George Frisby

- Norman Hicklin

- George Howe

- Albert Mee

- Giles Morgan

- Arthur Orridge

- Isaac Orridge

- Wallace Orridge

- Bert Palmer (possible)

- William Palmer (possible but there are 61 in CWGC)

- Arthur Sowter

- Arthur Thompson

- Benjamin Tomlin

- David Wain

I was unsuccessful in definitively finding the war graves of the following people, mostly because there were too many possible candidates:

- Frank Bexon − there were 8 Bexons in CWGC, 2 in Leicestershire Regiment but no Frank

- George or G Howe − there were 29 in CWGC, and 2 in Leicestershire Regiment

- A Mayes − there were 20 in CWGC but Barry was unable to supply a first name

- W Mayes − there were 16 in CWGC but again I had no first name

- S Nunn − there were 7 in CWGC but again I had no first name

It is important to note that none of those who are named on the sides of the Memorial have war graves, confirming that they did return.

One curiosity was G Frisby who seems to be buried in one place but remembered in another. If it is the same person, according to the records he is buried in the Wymondham (Leics) graveyard but is not commemorated on the memorial there. The records state:

FRISBY Charles George. Private 6029, 12th Training Battalion, Depot, Leicestershire Regiment. Died at home 21st February 1917. Born ymondham, enlisted Loughborough, resident Diseworth, Derbyshire. Buried in ST PETER CHURCHYARD, WYMONDHAM, Leicestershire.

Researching village names in the 1901 Census

Having confirmed that the War Memorial did indeed commemorate both the War Dead and those who returned safely, I then set about searching for 'village names'. My sources for this were:

- The 1901 Census, which can be accessed at findmypast.co.uk which is the official genealogy site of the Welsh & English census information for 1901 and operates on a pay per view basis.

- The Genealogy Website Ancestry at ancestry.co.uk which is a subscription website, which now has all the censuses from 1841 to 1901, as well as a wealth of other material.

In the end, of the men named on the War Memorial, I managed to find the following, although I would appreciate confirmation that they are correct as only initials are given on the Memorial. Years of birth are approximate.

Name Year of Birth Name Year of Birth Harold Bradley 1896 Ronald Arthur Mee 1896 Percy Will Cartright 1897 Ernest William Moore 1891 William Ferguson 1891 Herbert Rodvers Moore 1900 Jessie Wm Hanford 1891 Thomas Alfred Moore 1898 Arthur Joseph Harris 1896 Walter Moore 1894 John F Harris 1892 John Victears Morgan 1891 Charles Harris 1896 John Orridge 1887 Dimmock Howe 1896 Samuel Orridge 1900 Thomas A Howe 1897 Bertram Orridge 1883 Richard Lester 1890 Albert Poxon 1898 Jos W Kirby Locke 1888 George Poxon 1897 Oliver William Mee 1894 Arthur Edward Screaton 1896 There were a number of men that I couldn't find in the1901 census. In some cases I could find the families in the village but the men named on the memorial were not in the 1901 census so they may have been born later than March 31st 1901 when the census was taken, not be related or moved into the village later. Until we have the 1911 Census, which we have now been told will be released in 2009, it's not possible to check further. The families I found were:

- Barnetts living in Grimes Gate

- Blackwells who kept the Plough

- Bexons living in Lady Gate, although I found Frank in Derby

- Hudsons living in Hall Gate

There remaining 7 surnames that were not represented in the 1901 Census and these were:

- Baines

- Brisco

- Burton

- Hubbard

- Jackson

- Padwick

- Rushton

and it would be useful to have any information on these families.

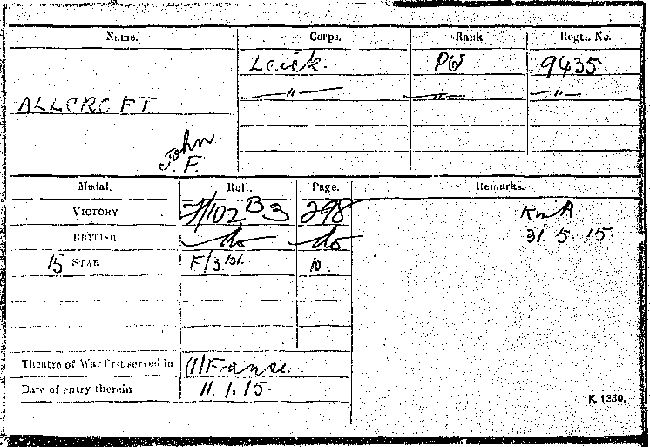

The Mysterious Private Allcroft

And now the mysterious Private Allcroft, who you recall is buried in the churchyard, but does not appear to be a "local". This is what we have from his death record. We also know he claimed to be 21 when he died giving us a year of birth of about 1894.

- Name: John Frederick Allcroft

- Rank: Private

- Serial No: 9435

- Battalion: 1st

- Cemetery or Memorial: Died of wounds

- Country: 1st

- How Died: Died of wounds

- Date of Death: 31 May 1915

- Conflict: World War 1

- Born: West Ham, Surrey

- Enlisted: Leicester

- Resident: Melbourne, Derbyshire

- Biographical Details: France & Flanders

National Archives, Catalogue Reference: WO/372/1 Image Reference:8973

This is his medal card, clearly showing that he was killed in action

National Archives, Catalogue Reference: WO/372/1 Image Reference:8973

This is his medal card, clearly showing that he was killed in action

This is his gravestone, in Diseworth churchyard

This is his gravestone, in Diseworth churchyard

Now one problem with this birthplace is that West Ham isn't in Surrey; it's either in Greater London or Essex. In trying to find out more about him I looked at the 1901 census and found that there was no John Frederick Allcroft at all in the census, but there were 2 possible John Allcrofts born between 1893 and 1896. One gave almost no information and the other seemed to be a John J Allcroft although with transcription errors this could have been an F. However, neither was born in West Ham.

On looking in more detail at the two entries it became apparent that John J wasn't 5 years old at the time of the census but 5 months and his year of birth had been wrongly transcribed. This revelation seemed to put him out of the frame unless of course he lied about his age and he was not 21 when he died but only 16.

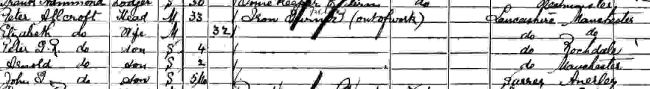

I therefore attempted to research this boy, but found that his family had no connection with Diseworth, or indeed Leicestershire. His father Peter had been born in Manchester in 1868 and following him back, his grandfather was Joseph, also born in Manchester in 1836, and his great grandfather was Peter, born in Staveley in 1810. I then found the registration of the boy John J's birth in the December quarter of 1900 in Croydon and he was clearly registered as John Thomas Allcroft (so not J) and certainly not Frederick. So that was the end of him as a candidate.

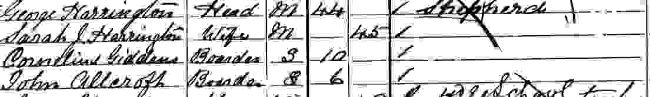

I therefore turned to the other John Allcroft, born around 1895 according to the 1901 census. His entry is annoyingly brief with no indication of where he was born.

George Harrington was a shepherd by occupation and even he is a bit of a mystery man, as he has a wife named Alice and family in the previous censuses, but by 1901 Alice has been replaced by Sarah and his two youngest daughters, Alice aged 12 and Rebecca aged 14 are living with separate relatives. His young son George, who would have been 10 by 1901 seems to have disappeared, probably dying in infancy.

But back to John Allcroft. In fact, despite the name sounding fairly common there were only 120 male Allcrofts in the whole of the 1901 England census and so I could look at all of them for possible matches, but there were no other candidates. I then checked all Allcroft births registered between 1893 and 1897 and found 23 Allcroft boys but non registered in West Ham and none of them registered as John Frederick. There is one John Malcolm Allcroft but he was registered in Rhayader in Wales in September 1896.

In the 1901 census there are 9 Allcrofts in Leicester, but none in Essex, so I can't follow up on his background on this basis. I then looked for other Allcroft connections to the village in the 1901 census, and found a James Allcroft living in Hodnet in Shropshire with his daughter, who had been born in Diseworth in 1832. He was a gamekeeper and I followed him back through the censuses until I found a whole family of them living on The Green, Diseworth in the 1841 census. Father, Edward, who wasn't born in the county, was also a gamekeeper. There is no sign of the family in the village by 1851 and I can't find them elsewhere either, but I picked up the threads of the children in later censuses as they moved around the country. There is little evidence of most of them by 1901 and there seems to be no connection with John Frederick. This therefore looks like another dead end and a simple coincidence.

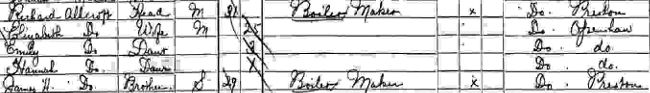

There does remain one remote possibility about the origins of John Frederick but they don't help to attach him to Diseworth. In the 1891 Census there was a Richard Allcroft (born in Preston in1861) living in West Ham

The entry states that in 1891 he was Married, but was lodging there alone, a boiler smith and born in Preston. However he was also included with his family at home in Lancashire:

I am sure it is the same person, as by 1901 he had returned to his home county of Lancashire and his family and the same names appear. Is it possible Richard was leading a double life? There is a gap in his children between Hannah born in 1890 and Richard born in 1894. Was he away from home a lot in the intervening years? Could he be the father of John Frederick?

Whilst looking for possible mothers for John Frederick I did find the death of a Fanny Allcroft in the December quarter of 1896, at which time John would have been about 2. She was aged about 44 so it of where he came from. Unfortunately I can't trace Fanny in the earlier censuses to explain why her death was registered in West Ham.

I also tried to find an Allcroft connection with Melbourne which is where John Frederick was resident before he signed up in Leicester. There were a total of 3,580 residents in Melbourne in the 1901 census but no connection with Allcroft or any name that could be confused with it so, again, this drew a blank.

As an aside, I also failed to find a entries for Cornelius Giddens in either the register of births or the 1891 census when he might have been present. There are no other Cornelius Giddens in any of the censuses although Giddens is not quite such an uncommon name as Allcroft with around 400 of them in the 1901 census. There were 198 boys called Cornelius born between 1899 and 1901 but no Giddens or anything like it. I also checked to see if he had died in the war but there were only 13 Giddens who died and he wasn't one of them. There was a C Giddings but he was too young to have been Cornelius. Yet another dead end.

From information from Annie Fletcher we do now believe that whoever John Frederick Allcroft was, he was in the area prior to the war working for the Jarrom family. Annie also said that they sent him to college to learn about agriculture. I tried to follow this up and started by assuming that he had been sent to what is now the part of Nottingham University located at Sutton Bonnington but which was originally in Kingston upon Soar. I discovered that in 1900 the agricultural department of University College, Nottingham, moved to Kingston and merged with the existing Dairy College to form "The Midland Agricultural and Dairy College". It provided various general and special courses to meet the requirements of different types of students. In addition much was done by consultations, analyses, and a travelling Dairy School was set up to advance these industries in the co-operating counties. I contacted the archivist but unfortunately all records from the early days have been destroyed, so there is no way of finding out more about John Frederick from this source.

I have racked my brain to find ways of discovering who John Frederick Allcroft was and why he came to Diseworth but I have to admit defeat, at least until the 1911 census is available and we possibly find him there.

Conclusions

My research has come up with a number of conclusions:

- All of the people on the War Memorial 'belong' to Diseworth with the possible exception of John Allcroft.

- The men listed in the centre panel headed 'RIP' died in service.

- The men listed on the outer panels returned home safely.

- John Allcroft was, most probably a 'foundling' or some other orphaned child, of which there were very many around that time, my grandmother included. He was probably farmed out to learn a trade, in his case agriculture.

- John Allcroft may have worked for the Jarroms before enlisting and may also have attended the Midlands Agricultural and Dairy College in Kingston upon Soar. It would be very nice to have more information from anyone who knows about the college early in the 20th century.

- Never trust anything without checking for yourself!

If anybody has any further information, or can shed light on any of the remaining questions, I would be pleased to hear from them.

Written by Meg Galley, September 2007

Addendum: The Orridge Family and the War Memorial

On the War Memorial in Diseworth there are 6 Orridge men mentioned, 3 in the central RIP panel and 3 in the outer panel. They are respectively:

- A (Arthur)

- I H (Isaac Henry )

- W (Wallace)

- G (George)

- J (John)

- S (Samuel)

However, after posting the original article on the Heritage Trust website, I was contacted by Mark Orridge from Melton Mowbray who believes that the names have been wrongly placed. He says in his email:

"I really enjoyed the fascinating article on the memorial. I have some information which I hope may help. In the centre RIP section of the memorial I have grave details for Isaac Harry Orridge who was killed 21/03/1918 and Arthur Orton Orridge who was killed 20/07/1916 but I have no grave records or medal details for Wallace Orridge. In the outer panels I have details of George Orridge being demobbed from the Navy in 1919,John W Orridge is listed as Leicestershire Regt. then Labour Corps so I assume he survived. Now here is the odd one out. Samuel Wallace Orridge, here are his details: Pte. 241598 5th Battalion Leics. Regt. died Sunday 11th February 1917 age 20.Grave D18 St Pol cemetery extention, Pas de Calais,France. It looks like the names of Wallace Orridge ;and Samuel Wallace Orridge have been mistakenly placed in the wrong panels! Their Father Samuel (brother to my Great Grandfather) was born in Wysall and became a Farm servant at the Jarrom Farm at Diseworth. He went on to marry the Farm owners daughter Mary Jarrom."

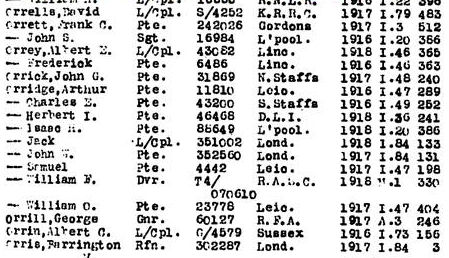

I have therefore gone back and re-looked at various sources to check out what he says. When I researched the names originally I thought that Wallace Orridge was W O Orridge who was killed on 17 June 1917 and was with the Leicestershire Regiment. However I have now checked W O Oridge in the 1901 census and it looks as if he is William Oliver and would probably have been a cousin of the Disworth Orridges as he lived in Wysall with his parents John and Agnes which is where the father of the Diseworth Orridges, Samuel came from. I looked at the records for war deaths in the Army (other ranks) for 1917 to 1921 and got the list shown below.

It does not have a Wallace Orridge as the only other W was W F Orridge who turned out to be 44 and had been a miner from Derbyshire. This added further confirmation to Mark's information that Wallace survived the War. I also checked again on the War Graves website and found Samuel, although I am not sure why I didn't find him before. All of the three Orridge sons who died are shown on the table below:

Surname Rank Service no. Date of Death Age Regiment Nationality Buried ORRIDGE, ISAAC HENRY Private 88649 21/03/1918 Unknown The King's (Liverpool Regiment) UK Pozieres Memorial ORRIDGE, A O Private 11810 20/07/1916 Unknown Leics Regt UK St Sever Cemetery, Rouen ORRIDGE, S W Private 241598 11/02/1917 20 Leics Regt UK St Pol Communal Cemetery extension The records of the Orridge Deaths from the Commonwealth War Graves and on the Certificate from the War Graves Commission S W Orridge is stated as being the son of Samuel and Mary Ann Orridge of Page Lane, Diseworth so there is not doubt about it.

I am therefore left with the conclusion that Mark is correct and Wallace Orridge survived and should be on the outer panel whilst Samuel did not and should be in the Central 'RIP' panel. I thought it would be a nice gesture if Samuel's name could be added to the list that is read out on Remembrance Sunday and I am pleased to say that it happened in November 2007 thanks to Barry Smith. What I do find odd is that nobody said anything at the time. Perhaps they did and it has just not been passed down to us. Perhaps the family had all left the village by the time the Memorial was erected. Perhaps someone knows.

Written by Meg Galley, Nevember 2007

Addendum: Frank Bexon and the War Memorial

When I did the original research for the War Memorial I reported that I had been unsuccessful in definitively finding the war grave of Frank Bexon as there were 8 Bexons in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, 2 in Leicestershire Regiment but no Frank. However, since then I have been contacted by Richard Taylor whose wife was a Bexon and he confirmed that Frank was living in Derby by 1901, which I had found out, and that in August 1913 he emigrated to Canada. I have found the record of his voyage and he went out with his mother Sarah and his sisters Lois and Dora. His brother Edwin had already emigrated in 1911.

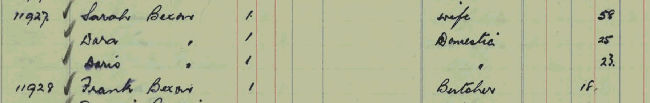

Original Entry showing Frank and his family emigrating to Canada.

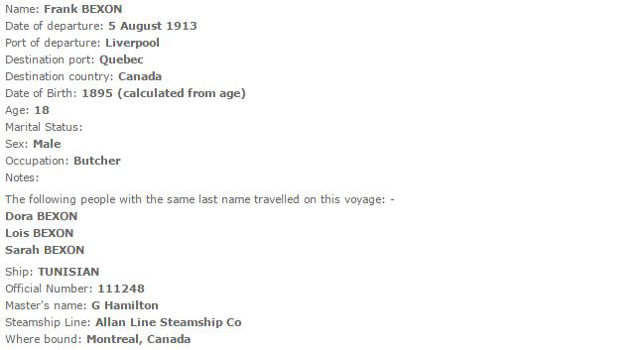

Details of the ship on which Frank and his family emigrating to Canada

I could find no record of his father emigrating and on checking deaths I note that he died in 1903, something confirmed by Richard Taylor.

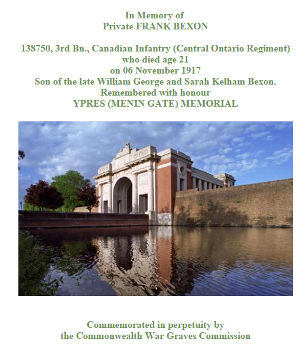

Frank then joined the Canadian Expeditionary Forces and sadly was killed at Passchendaele on 6 November 1917. This is recorded on the CWGC website with the following certificate that confirms that his father is dead at the time.

The Bexon Family

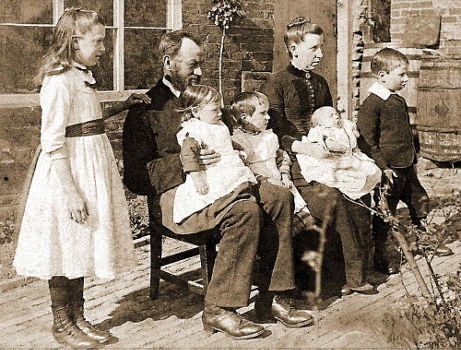

Richard also supplied some photographs of the Bexon family. This is a family group including Frank's father William George Bexon and mother Sarah Kelham Adkin taken about 1892, 3 years before Frank was born.

The Bexon Family around 1892

The Bexon Family around 1892

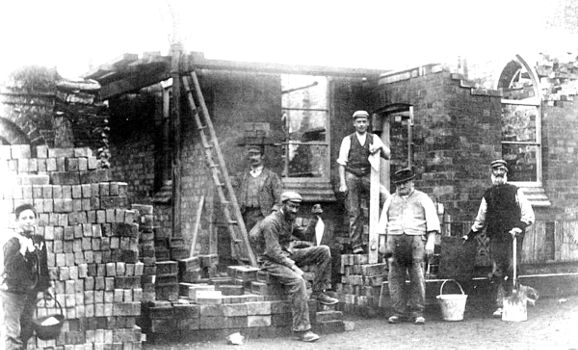

There is also a photograph of William Bexon working on a building but we have no idea where it is. Bexon family history says it is Diseworth Chapel but it clearly is neither the Lady Gate nor the Hall Gate Chapel.

William Bexon (centre with trowel) on a building site

William Bexon (centre with trowel) on a building site

If anyone knows where it is we would love to know.

Written by Meg Galley, August 2008

- Long Whatton Parish Registers

The quality of the original document was, in parts, poor. This was especially so at some page edges such that either the first name or the date was sometimes difficult to read. The section from 1643 onwards was particularly poor with whole sections being illegible. No records were legible for 1649. Where I have made an educated guess at a name or word I have included this in [Smith]. Where I have been unable to decipher a word or name I have recorded this as [ ]. I have made every effort to ensure the transcription is accurate but, as with all transcriptions, errors may have been made. The original document should always be checked to verify the data given.

Bishops Transcripts are available for some years and I have used these to verify the data given. Where extra or different information is provided in the BTs I have given this in red. No data was recorded for 1625 but BTs were. Hence all data for this year is given in red.

The index is just that and extra information will be available in the transcription. It is worth noting that the spellings of both first and surnames were variable, and sometimes a shorthand version was used, eg Coup, Cowp or Cowper for Cooper. Therefore in using the index it is worth searching all names which start with the same letter you are researching to see if variants exist. Also search names beginning with H if the name you are searching starts with a vowel. Similarly if the name you are researching begins with an H try searching for variants starting with the second letter, eg Umphrey for Humphrey.

The year given in the index is the year in which the event was recorded and is not necessarily the year in which the event took place. Also events were not always recorded chronologically. In general events were not recorded separately but recorded in roughly the order they occurred. It is worth noting that throughout this period the first of the year was recognised as March 25, hence events recorded from January 1 to March 24 would be the year previous to what we would use today. For example February 17 1600 would be regarded as in 1601 today.

Download PDF: Parish Records 1549-1653.pdf

Download PDF: Parish Records 1653-1700.pdf

- William Lilly

William Lilly (1602–1681) was born in Diseworth and became a famous astrologer and occultist. His prediction of the Great Fire of London (1666), fourteen years before the event, led to a popular suspicion that he had started it, and to a trial for the offence before Parliament, but he was found innocent. Read more about William Lilly and his work here.

His birthplace (Lilly's Cottage) stands at the Cross, between Lady Gate and Hall Gate, and was at one time used as a meeting-house by the first Diseworth Baptist community, before the Chapel was built.

The following is an extract from his autobiography, written in about 1668, in which he describes his early years in Diseworth, prior to his departure for London at the age of eighteen. It gives a vivid picture of life in the village in the early seventeenth century.

The Life of William Lilly, Student in Astrology

Wrote by himself in the 66th Year of his Age, at Hersham, in the Parish of Walton-upon-Thames, in the County of Surry. Propria Manu.

I was born in the county of Leicester, in an obscure town, in the north-west borders thereof, called Diseworth, seven miles south of the town of Derby, one mile from Castle-Donnington, a town of great rudeness, wherein it is not remembered that any of the farmers thereof did ever educate any of their sons to learning, only my grandfather sent his younger son to Cambridge, whose name was Robert Lilly, and died Vicar of Cambden in Gloucestershire, about 1640.

The town of Diseworth did formerly belong unto the Lord Seagrave, for there is one record in the hands of my cousin Melborn Williamson, which mentions one acre of land abutting north upon the gates of the Lord Seagrave; and there is one close, called Hall-close, wherein the ruins of some ancient buildings appear, and particularly where the dove-house stood; and there is also the ruins of decayed fish-ponds and other outhouses. This town came at length to be the inheritance of Margaret, Countess of Richmond, mother of Henry VII. which Margaret gave this town and lordship of Diseworth unto Christ's College in Cambridge, the Master and Fellows whereof have ever since, and at present, enjoy and possess it.

In the church of this town there is but one monument, and that is a white marble stone, now almost broken to pieces, which was placed there by Robert Lilly, my grandfather, in memory of Jane his wife, the daughter of Mr. Poole of Dalby, in the same county, a family now quite extinguished. My grandmother's brother was Mr. Henry Poole, one of the Knights of Rhodes, or Templars, who being a soldier at Rhodes at the taking thereof by Solyman the Magnificent, and escaping with his life, came afterwards to England, and married the Lady Parron or Perham, of Oxfordshire, and was called, during his life, Sir Henry Poole. William Poole the Astrologer knew him very well, and remembers him to have been a very tall person, and reputed of great strength in his younger years.

The impropriation of this town of Diseworth was formerly the inheritance of three sisters, whereof two became votaries; one in the nunnery of Langly in the parish of Diseworth, valued at the suppression, I mean the whole nunnery, at thirty-two pounds per annum, and this sister's part is yet enjoyed by the family of the Grayes, who now, and for some years past, have the enjoyment and possession of all the lands formerly belonging to the nunnery in the parish of Diseworth, and are at present of the yearly value of three hundred and fifty pounds per annum. One of the sisters gave her part of the great tithes unto a religious house in Bredon upon the Hill; and, as the inhabitants report, became a religious person afterwards.

The third sister married, and her part of the tithes in succeeding ages became the Earl of Huntingdon's, who not many years since sold it to one of his servants.

The donation of the vicarage is in the gift of the Grayes of Langley, unto whom they pay yearly, (I mean unto the Vicar) as I am informed, six pounds per annum. Very lately some charitable citizens have purchased one-third portion of the tithes, and given it for a maintenance of a preaching minister, and it is now of the value of about fifty pounds per annum.

There have been two hermitages in this parish; the last hermit was well remembered by one Thomas Cooke, a very ancient inhabitant, who in my younger years acquainted me therewith.

This town of Diseworth is divided into three parishes; one part belongs under Locington, in which part standeth my father's house, over-against the west end of the steeple, in which I was born: some other farms are in the parish of Bredon, the rest in the parish of Diseworth.

In this town, but in the parish of Lockington, was I born, the first day of May 1602.

My father's name was William Lilly, son of Robert, the son of Robert, the son of Rowland, etc. My mother was Alice, the daughter of Edward Barham, of Fiskerton Mills, in Nottinghamshire, two miles from Newark upon Trent: this Edward Barham was born in Norwich, and well remembered the rebellion of Kett the Tanner, in the days of Edward VI.

Our family have continued many ages in this town as yeomen; besides the farm my father and his ancestors lived in, both my father and grandfather had much free land, and many houses in the town, not belonging to the college, as the farm wherein they were all born doth, and is now at this present of the value of forty pounds per annum, and in possession of my brother's son; but the freehold land and houses, formerly purchased by my ancestors, were all sold by my grandfather and father; so that now our family depend wholly upon a college lease. Of my infancy I can speak little, only I do remember that in the fourth year of my age I had the measles.

I was, during my minority, put to learn at such schools, and of such masters, as the rudeness of the place and country afforded; my mother intending I should be a scholar from my infancy, seeing my father's back-slidings in the world, and no hopes by plain husbandry to recruit a decayed estate; therefore upon Trinity Tuesday, 1613, my father had me to Ashby de la Zouch, to be instructed by one Mr. John Brinsley; one, in those times, of great abilities for instruction of youth in the Latin and Greek tongues; he was very severe in his life and conversation, and did breed up many scholars for the universities: in religion he was a strict Puritan, not conformable wholly to the ceremonies of the Church of England. In this town of Ashby de la Zouch, for many years together, Mr. Arthur Hildersham exercised his ministry at my being there; and all the while I continued at Ashby, he was silenced. This is that famous Hildersham, who left behind him a commentary on the fifty-first psalm; as also many sermons upon the fourth of John, both which are printed; he was an excellent textuary, of exemplary life, pleasant in discourse, a strong enemy to the Brownists, and dissented not from the Church of England in any article of faith, but only about wearing the surplice, baptizing with the cross, and kneeling at the sacrament; most of the people in town were directed by his judgement, and so continued, and yet do continue presbyterianly affected; for when the Lord of Loughborough in 1642, 1643, 1644, and 1645, had his garrison in that town, if by chance at any time any troops of horse had lodged within the town, though they came late at night to their quarters; yet would one or other of the town presently give Sir John Gell of Derby notice, so that ere next morning most of his Majesty's troops were seized in their lodgings, which moved the Lord of Loughborough merrily to say, there was not a fart let in Ashby, but it was presently carried to Derby.

The several authors I there learned were these, viz. Sententiæ Pueriles, Cato, Corderius, Æsop's Fables, Tully's Offices, Ovid de Tristibus; lastly, Virgil, then Horace; as also Camden's Greek Grammar, Theognis and Homer's Iliads: I was only entered into Udall's Hebrew Grammar; he never taught logick, but often would say it was fit to be learned in the universities.

In the fourteenth year of my age, by a fellow scholar of swarth, black complexion, I had like to have my right eye beaten out as we were at play; the same year, about Michaelmas, I got a surfeit, and thereupon a fever, by eating beech-nuts.

In the sixteenth year of my age I was exceedingly troubled in my dreams concerning my salvation and damnation, and also concerning the safety and destruction of the souls of my father and mother; in the nights I frequently wept, prayed and mourned, for fear my sins might offend God.

In the seventeenth year of my age my mother died.

In the eighteenth year of my age my master Brinsley was enforced from keeping school, being persecuted by the Bishop's officers; he came to London, and then lectured in London, where he afterwards died. In this year, by reason of my father's poverty, I was also enforced to leave school, and so came to my father's house, where I lived in much penury for one year, and taught school one quarter of a year, until God's providence provided better for me.

For the two last years of my being at school, I was of the highest form in the school, and chiefest of that form; I could then speak Latin as well as English; could make extempore verses upon any theme; all kinds of verses, hexameter, pentameter, phaleuciacks, iambicks, sapphicks, etc. so that if any scholars from remote schools came to dispute, I was ringleader to dispute with them; I could cap verses, etc. If any minister came to examine us, I was brought forth against him, nor would I argue with him unless in the Latin tongue, which I found few of them could well speak without breaking Priscian's head; which, if once they did, I would complain to my master, Non bene intelligit linguam Latinam, nec prorsus loquitur. In the derivation of words, I found most of them defective, nor indeed were any of them good grammarians: all and every of those scholars who were of my form and standing, went to Cambridge and proved excellent divines, only poor I, William Lilly, was not so happy; fortune then frowning upon father's present condition, he not in any capacity to maintain me at the university.

Of The Manner How I Came Unto London

Worthy sir, I take much delight to recount unto you, even all and every circumstance of my life, whether good, moderate, or evil; Deo gloria.

My father had one Samuel Smatty for his Attorney, unto whom I went sundry times with letters, who perceiving I was a scholar, and that I lived miserably in the country, losing my time, nor any ways likely to do better, if I continued there; pitying my condition, he sent word for me to come and speak with him, and told me that he had lately been at London, where there was a gentleman wanted a youth, to attend him and his wife, who could write, etc.

I acquainted my father with it, who was very willing to be rid of me, for I could not work, drive the plough, or endure any country labour; my father oft would say, I was good for nothing.

I had only twenty shillings, and no more, to buy me a new suit, hose, doublet, etc. my doublet was fustian: I repaired to Mr. Smatty, when I was accoutred, for a letter to my master, which he gave me.

Upon Monday, April 3, 1620, I departed from Diseworth, and came to Leicester: but I must acquaint you, that before I came away I visited my friends, amongst whom I had given me about ten shillings, which was a great comfort unto me. On Tuesday, April the 4th, I took leave of my father, then in Leicester gaol for debt, and came along with Bradshaw the carrier, the same person with whom many of the Duke of Buckingham's kindred had come up with. Hark how the waggons crack with their rich lading! It was a very stormy week, cold and uncomfortable: I footed it all along; we could not reach London until Palm-Sunday, the 9th of April, about half an hour after three in the afternoon, at which time we entered Smithfield. When I had gratified the carrier and his servants, I had seven shillings and sixpence left, and no more; one suit of cloaths upon my back, two shirts, three bands, one pair of shoes, and as many stockings. Upon the delivery of my letter my master entertained me, and next day bought me a new cloak, of which you may imagine (good Esquire) whether I was not proud of; besides, I saw and eat good white bread, contrary to our diet in Leicestershire. My master's name was Gilbert Wright, born at Market Bosworth in Leicestershire; my mistress was born at Ashby de la Zouch, in the same county, and in the town where I had gone to school. This Gilbert Wright could neither write nor read: he lived upon his annual rents, was of no calling or profession; he had for many years been servant to the Lady Pawlet in Hertfordshire; and when Serjeant Puckering was made Lord keeper, he made him keeper of his lodgings at Whitehall. When Sir Thomas Egerton was made Lord Chancellor, he entertained him in the same place; and when he married a widow in Newgate Market, the Lord Chancellor recommended him to the company of Salters, London, to admit him into their company, and so they did, and my master in 1624, was master of that company; he was a man of excellent natural parts, and would speak publickly upon any occasion very rationally and to the purpose. I write this, that the world may know he was no taylor, or myself of that or any other calling or profession: my work was to go before my master to church; to attend my master when he went abroad; to make clean his shoes; sweep the street; help to drive bucks when he washed; fetch water in a tub from the Thames: I have helped to carry eighteen tubs of water in one morning; weed the garden; all manner of drudgeries I willingly performed; scrape trenchers, etc. If I had any profession, it was of this nature: I should never have denied being a taylor, had I been one; for there is no calling so base, which by God's mercy may not afford a livelihood; and had not my master entertained me, I would have been of a very mean profession ere I would have returned into the country again; so here ends the actions of eighteen years of my life.

------------

(Extracted from The Project Gutenberg EBook of "William Lilly's History of His Life and Times, by William Lilly". This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at gutenberg.net.

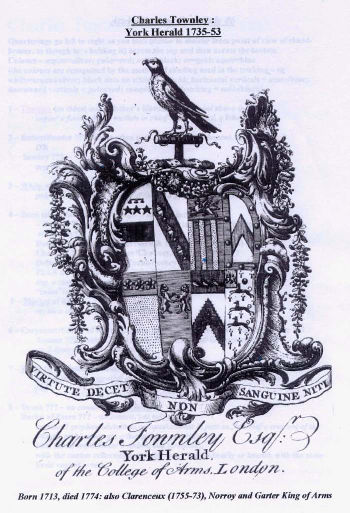

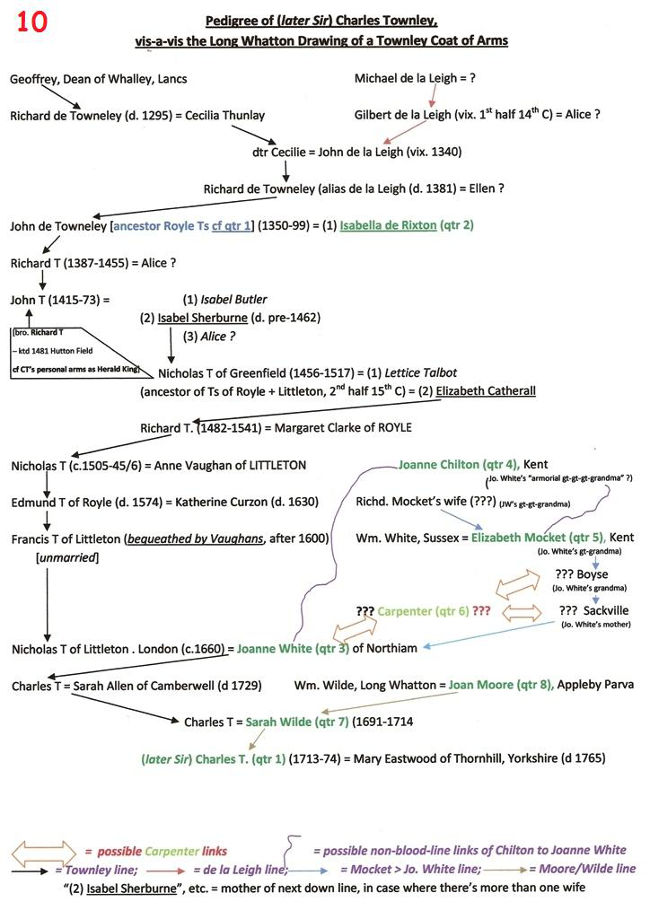

- Townley Arms

The Townleys and the Manor House, Long Whatton

The tall house opposite The Falcon pub in Long Whatton is known as The Manor House. From 1753 until 1945 it was home to generations of the Townley family. Before 1753 it had been a simple farmhouse with a fair bit of land behind, but when Charles Townley brought his young wife here to live, he put a grand 'Georgian' extension on it. Charles was a London boy, the son of a merchant. But his mother had been a Long Whatton girl, daughter to William Wilde, Gent. of Long Whatton. So it is possible the house and farm belonged at one time to Charles's mother or his grandfather. Whatever the case, the Townley family lived in the house for nearly 200 years, and descendants of the family still live in the village. Charles himself continued to work in London, rising to the position of Garter King at Arms, and being knighted by King George III. The crest of the Townley family in Long Whatton is a falcon.

Preamble by Val Stevens

The Desire for Recognition

We are dealing with a coat of arms related to a premier herald: his role in that craft or profession would be used to create a shield like the one found as an engraving (or drawing) in Long Whatton, and pictured here.

Heraldry is attractive visually, essentially in its DESIGN features, and this attraction seems a motive for this illustration.

History & Genealogy, though, are also part of studying heraldry:

(a) to find the heraldic reasons for any particular design or multi-combination of designs – especially in this Townley engraving or drawing; and

(b) to show political / social purposes, beyond simple visual recognition.

Such considerations, which seem to have motivated Charles Townley also, are a key to how heraldry originated as a means of Recognition, both in its perhaps over-emphasised military or tournament elements and in how a person's place in society is displayed by his/her coat of arms.

What might have become a conflict in the purpose of heraldry – Recognition for Allegiance / Rallying – i.e. in War or Jousts, versus Recognition for Display / Statement – i.e. in placing someone distinctively in a social rank - can be resolved by acknowledging that they are interlinked, and would come together in warfare for strategic political bargaining (i.e. ransom), not necessarily for a full financial return, but to ensure that campaign gains were retained and key opposition players were kept out of further action.

In the absence of real or feigned fighting, of course, recognition was certainly still important, but for STATUS / DEFINITION: your coat makes clear who you are and what your antecedents are – this is especially telling with respect to our Townley engraving, and would be particularly important in the 16th/17th/18th Centuries, with the proliferating rise of the gentry and the significance of arms for "Families of Consideration". This latter phrase I found in correspondence about position and connections while researching the wonderful set of coats of arms decorating the hallway in Thrumpton Hall, Nottinghamshire. A 1789 letter between John Wescomb Emerton and his brother Nicholas (married to Lucy Marshall) is about arrangements for painting onto a coach the combined Wescomb-Marshall escutcheon. One half of these arms is shown in figure 01 at right:

These Marshall arms are clearly of the branch of the family marrying into the Wescomb-Emerton line owning Thrumpton at this time, with prestigious descent from the famous William, Earl of Pembroke, Marshall of the Realm under Henry II, and virtual Regent in Henry III's minority.

However, a shock for John Wescomb Emerton: in the arms on Nicholas's landau , the gold and green halves had been reversed. In the same run of correspondence, John Wescomb Emerton also notices that the Wescombs have been using wrongly-reversed arms for their own Somerset forebears, proven by referring to the house copy of the 18th Century Edmondson's "Heraldry". This sadly caps other Wescomb-Emerton family-members' lifetime of searching for correctness and authenticity, and for "Consideration": John's despairing final cry is: "How came we to reverse it?"

Again, display / statement is the point here – "Here I am – know me for who I am and what I bring with me or inherit": I'll explain later this concept of "bringing with me", the key to understanding heraldry, & especially how a shield like our engraving is created – who you are, and what heraldic inheritance you "bring with you". The centre and raison-d'être of an Achievement, though, is the shield, and without it you can't have the full collection of heraldic display that an armiger (who can legitimately bear an authenticated coat of arms) can claim– you see an Achievement in our Townley arms here – shield, crest, mantling and motto – almost the full works!

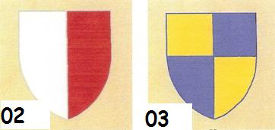

A simple shield nowadays seems very rare, perhaps unknown - i.e., a more complex shield stems from the need to define yourself clearly against others – Saxon / Viking shields were often depicted one-colour, but from quite early medieval times at least one other colour is usually found. The simplest variation is to divide the shield, and I'll use a couple of names you'll recognise from history and literature as examples – e.g. halves (parti per pale – in figure 02: Waldegrave – the shield is blazoned as per pale argent & gules), or quarters (quarterly - in figure 03: Falstaff – quarterly or & azure)

Recent contact with the College of Arms tells us that the family shield of Sir Charles Townley (both his father and grandfather were also named "Charles"), when our man became knighted as Garter King of Arms, was superficially like 03 above, recorded as follows: quarterly, 1 & 4 Townley; and 2 & 3 Wilde. Although we come later to look closely at the Charles Townley multi-shield, for the moment it is enough to say that I have used the word "superficially" above because the reasons for the quartering are different - 03 is a simple colour-combination, whereas the "official" Townley-Wilde shield at the College of Arms is to record, by quartering, each part of our subject's lineage via his father's and his mother's families.

For example, divisions into sixths (quarterly of six) must not be confused with the simple division of a shield. As in the case of our Townley engraving (quarterly of eight), we have the use of multiple divisions (sometimes only two or four) as a way of including, via marriages, OTHER coats of arms, not just a way of dividing up colours – if any of the coats that make up quarters also contain quarters, then they could be included too – that's not our problem here – BUT there is a famous, perhaps ultimately pointless, example of a coat of 322 (!) subordinate coats, Lloyd of Stockton, where intermarriages with cousins in other branches of the same families way back into Welsh history / legend mean that the same quarters keep turning up. How this multiplicity of coats could all come about should be clearer when we later look more closely at the Townley coat concerning us here.

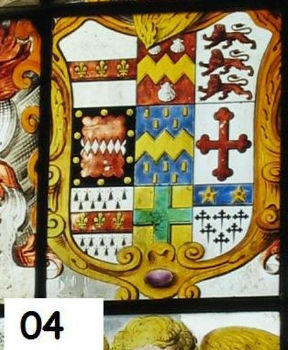

A comparable display to our Townley coat of arms is found at Flintham Church, Nottinghamshire, for the Disneys – see figure 04 at right:

This chancel window represents the line of the family up to Daniel Disney (1656-1734), Kirton & Lincoln, who became Vicar of Swinderby, Lincs, held the living of Flintham Church, and owned the Hall beside it for a time.

The 9 "quarters" (in order, top > bottom, left > right) represent:

- Disney of Swinderby & Norton Disney, Notts (i.e. Daniel's father's branch of origin)

- Dive (the earliest noble marriage into the family;

- Disney of Lincoln (a coat brought in by the Dives, derived from Amundeville, who handed over their Conquest possessions to the Dives);

- Neville of Notts (arguably);

- D'Eyncourt of Lincs/Yorks;

- Crosholme of Notts;

- Harbin of Lincs;

- Hussey of Notts;

- Clinton of Notts

(all are in this Disney line, up to the 18th century).

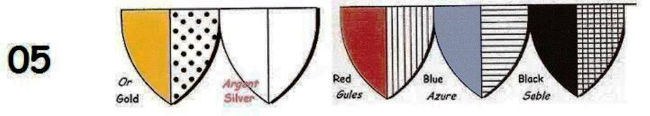

In other words, your shield reflects the marriages in your line with the women of other armigerent families, starting with the earliest known up to most recent times. Whereas, like so many depictions of arms, the Disney coat above is in glorious technicolour, our Townley achievement is in shadings / hatchings of various sorts: the type of shading indicates the colour, so a drawing or engraving such as this can be used as a black-and-white plan for a coloured plaque, flag, piece of stained glass, or whatever – the hatching/shadings are as in 05 below.

and the fur ermine is drawn with black spots on white, as in the field of qtr 8 of the Charles Townley drawing. It is worth commenting on the Sable hatching of the first Townley quarter (qtr 1) – it should be dense cross-hatching, BUT on our engraving it so much so that it looks almost solid - there is maybe some covering up here – do you see signs of some other full colouring showing through in qtr 1? – this may be significant in what I say later about the design Charles Townley created. Hatching is therefore often a clue as to how to "read" shields (and other aspects of an Achievement) if they are created on stone, wood, metal, or other carved, engraved or moulded media.

Crests, Mantling, Mottos

Taken together, these, with the shield, make up what is called, in the technical heraldic sense only, the armiger's Achievement – it does not refer to deeds of prowess. As you can see in the illustration, there is more to the whole achievement than the shield, but everything else is really there only to tell us more about the shield and its owner.

The Crest first of all. Not everyone has one, and crests are shared by disparate and unconnected armigerents – they seem chosen at will, provided the College of Arms accepts your right to have one. Theoretically a crest should have a helmet to stand on, but, as we see with this Townley shield, there is no helm, because, at this time, Charles Townley is not yet even gentry.

Why the falcon is chosen by Charles Townley, I am not sure, although I believe that there exists some sort of reference to his being "falconer to the king" – it would seem appropriate, though, that there is a pub called "The Falcon", near where Charles Townley found his in-laws in Long Whatton. Charles Townley, who should know, as a herald (but … watch this space! ), merely has, in our shield, the device of a perch to hold the bird, which is at least logical and aesthetically pleasing, although the perch is itself impossibly perched on a wreath or torse of what looks like black and ermine (or red and ermine, maybe to reflect the red in the Moore colours - Fairbairn's "Crests" describes the Townley crest as also having a red ribbon round the perch). The two tinctures for the torse, as for Mantling, are what are known as livery colours, and survive in horse-racing.

The Mantling (sometimes called the Lambrequin) should dangle from the helmet of an arms-bearer. In our coat, it seems more like a floral decoration, whereas it is generally thought now to be a stylised version of the cloth Crusaders would wear to protect their necks, perhaps the whole helmet, against the sun – it would, in the course of a campaign, soon be in tatters, so would come to look at times like rags or even vegetation, a bit like acanthus leaves, which would be consistent with the style of drawing mantling in the first part of the 18th Century, with even garlands of flowers draped round it, as here. It is usually in the two main, livery tinctures of the shield - for Townley in qtr 1, and in several of the sub-shields, this should be black and white (although here the pattern is indistinct and perhaps just decorative). Mantling should be from a helm, but Charles Townley has possibly gone against heraldic commonsense and used his imagination here to show mantling apparently growing out of the shield itself, and clearly not from the torse, which would have been used to hold the mantling in place.

Mottos are not obligatory, but several people have them, and they are often shared. The meaning for Townley seems to be "it is more fitting to be virtuous than noble in blood" - the implication that blood alone won't make you a good man suits someone whose honours came more by virtue of his work than by birth. If you look up the Townley motto, though, you will find probitas verus honos, and also tenez le vraye, which imply much the same as we have here, so it looks as if Charles Townley was perhaps ringing the changes a little in order to provide a bit of distinction for himself. There may be, as we shall see, a touch of unwitting irony in Charles Townley's choice of motto.

Heralds – College of Arms, Heralds' role, characters, power

Heralds probably began as messengers of landowners, especially with estates all over a region, the likely origin of their having recognisable coats (tabards), and of their thus having certain rights of access and self-protection. This diplomatic role eventually made them arbiters of custom, conduct and outcomes in battles and tourneys (you may recall Mountjoy, the French herald in Shakespeare's play, the epitome of courtesy and authenticity in acknowledging the claims of Henry V's victory in the Battle of Agincourt). From this position heralds developed the role of authentication of rights of armigers to bear the arms they claimed, which added a significant political and social dimension to their work or position.

This role of authentication became developed into the system of supervision descending from the College of Arms (chartered by Richard III), where the Earl Marshall heads a system that grants arms and oversees heraldic usage and practice in England and Wales – let us now look at the way in which our Charles Townley may have been involved in this system as it operated in his time.

At the time of our Achievement, he was simply York Herald. In this role, he was inferior, in rank if not in independence of action, to Norroy, the Herald King who looked after England roughly north of the Trent, and superior to the lesser Pursuivants. While our Charles Townley was York Herald, he appears to have made many sketches or drawings related to his office (some of which I believe are held in Long Whatton), and our Achievement here is probably one of these. What sort of a herald was he? Hard to say for sure, but we can look at the sort of heralds there were at the end of a truly critical period of English history: as a perhaps undesirable consequence of a movement we may shorthand as "The Rise of the Gentry", in which society changed through many inter-linking movements, a whole new world wanted to use armorial display, not least to define position and possessions.

Thus, the procedure of heraldic Visitations during the 16th and 17th Centuries became a vital method of authenticating your arms and whether you should have them. Heralds were put into a position of great power and potential corruption, and, to some, self-importance seems to have overcome ethics: there is some suspicion about their total commitment to altruism. Let's pause here to look at Sir Charles Townley's personal / family coat (see figure 06 below) adopted while in his position as Garter King:

It is clearly different from the usual or "general" Townley arms (as in qtr 1 of the engraving), in that another mullet (star) or has been added to the otherwise plain fess (broad horizontal band) sable – it uses an existing element in a new way, and an annulet (ring) gules has been superimposed. Here, Sir Charles Townley (years after the Achievement we are largely discussing here) has made a distinct change, and it might be assumed that he has in some way wanted to mark his position more. Sir Charles Townley, by virtue of his job, seems consistent with a trend of 16th to early 18th Centuries heralds to make a mark to show gentrification via office?

What is even more interesting is that Sir Charles Townley has used, not the general Townley coat, as we see in the Long Whatton achievement, but a development of the specific one granted, I believe, by Lord Stanley, when, at the Battle of Hutton Field in 1481, he knighted Sir Richard Townley. (an ancestor, by his marriage to Margaret Clarke of ROYLE, of Charles Townley's branch of Townleys) on behalf of Edward IV - here the plain black fess was differenced by a single silver star, not the gold one here. The College of Arms recognises the coat depicted above, but does not specify the colour or arrangement of star or ring, which may have been guessed by the designer. We might speculate whether the possible covering-up in the hatching of qtr 1 in our coat is, in fact, a shading-out of an earlier attempt to make an unauthorised (or maybe just experimental) change to the basic Townley shield before Charles Townley's marriage and later elevation to superior positions in the heraldic hierarchy.

As a herald, and especially later as Clarenceux Herald (southern England) & then Garter King, Charles Townley would have practised and authorised a major part of heraldic genealogy – the Marshalling of "multi-shields".

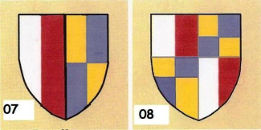

"Marshalling" is the skill of arranging the parts of a coat of arms to reflect accurately the lines of armorial heritage that any armiger can legitimately claim. The method is as follows: in its simple form, if a man marries a wife who is of a family that bears arms, such as, hypothetically, a Waldegrave man marrying a Falstaff woman (see figures 02 & 03 above), these are the results relevant to our case here: if the wife is a non-heiress, the arrangement is blazoned as parti per pale/ impaled – eg, a Waldegrave marries a Falstaff non-Heiress (see figure 07):

In its simplest form, Waldegrave-Falstaff descendants of this marriage would bear coat as in figure 08 above.

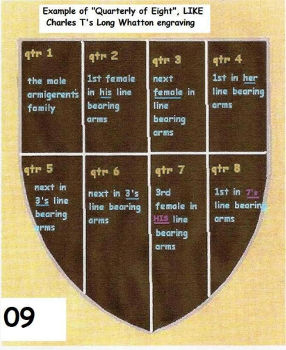

Logically, you might find this sort of quartering repeating itself but it becomes unwieldy (as in the Lloyds coat mentioned above). Sir Charles Townley in our shield simply and meaningfully tries to show the discrete coats of other "families of consideration" which play a part in his own blood line. The principles for such choices emerge as follows, if we look at this diagram of the possibilities of our shield – here is a hypothetical distribution (see figure 09). The principle is to look for the furthest back you can go to see which wives "bring in" their father's arms, or to look for the next female marrying in down the line who "brings in" her father's arms.

Now let's look at the details of this family scenario in our actual Long Whatton engraving. We seem to have:

Qtr 1 - Sir Charles's branch of the line are known as the Townleys / Towneleys / Thunlays, etc., of Royle in Lancashire, descended from a very ancient line where surnames became slightly changed as inheritances were passed on. Because, at the time of creating the drawing, Charles Townley was the eldest son of his father while his father was still alive (hence the label gules – the "toothed" red bar overlaying the top), he has the arms blazoned: argent a fess sable, three mullets in chief of the second, a label gules.

Qtr 2 – the first female marrying into the Royle line of Townleys is Isabella de Rixton, who marries John Towneley in the second half of the 14th Century – she brings in her father's arms of - argent, on a bend sable three covered cups of the field.

Qtr 3 – next to bring in arms is Joanne White, who married Nicholas Townley of Littleton, Middlesex (now in Surrey, near Shepperton Studios – by this time a number of Royle Townleys had moved south in solid middle-class professions, and the surname spelling had largely dropped the first "e") – he is great grandfather of our Charles Townley. The arms Joanne White brings in are – paly of six or and azure, on a chief of the second a griffin passant as the first.

Qtr 4 – a tricky one, although the attribution is clear enough - Chilton: or, on a chevron gules three cinquefoils of the field, on a bordure azure 10 bezants [This coat presents intricacies too complex to comment on here: they can be summarised by saying that the line from Chiltons to the Qtr 5 father of Elizabeth Mocket is only by virtue of her being co-heir with a sister who can claim Joanne Chilton as a great-great-grandmother; that the Chilton coat should follow Mocket (ie qtrs 4 & 5 should be in reverse order), since this Chilton ancestor is "brought in" by Mocket; and that the particular way in which the bordure is elaborated suggest association or patronage, rather than direct blood-line, thus probably making Joanne Chilton a kind of "armorial ancestor-cum-patron", a sort of feudal dependence.

Qtr 5 – Elizabeth Mocket married William White, part of the line leading down to Joanne White's marriage to Nicholas Townley, the great grandfather of our Charles Townley, the likely designer of our shield. or, on a chief azure, three cinquefoils of the first.

Qtr 6 – this coat is hard to relate to any history or pedigree of anyone mentioned so far – the attribution is pretty conclusively for the name Carpenter or Carter, both of whom are : azure, two lions rampant combatant or [There are some teasing suggestions of Carpenters in legal collaborations involving Whites, but the coat should therefore come after White (qtr 3), who would have "brought it in". My guess is that Carpenter is therefore included as someone whom the line of White + Mocket >>> White + Townley depended on in some way, again, another kind of prestigious association or feudal patronage] [At Thrumpton Hall, mentioned above, whilst there is no multi-coat like our Townley shield here, we do find two or three shields in the display of family arms that are not of relations, but clearly of wealthy associates.] The next two, though, are very clear:

Qtr 7 – Charles Townley's father married into the Wilde family of Long Whatton, and the rest, as they (and particularly yourselves) would say, is history – the coat is blazoned: argent, a chevron engrailed sable, on a chief of the second three martlets of the field.

Qtr 8 – "brought in" by Sarah Wilde is her mother, Joan Moore, from Appleby Parva, and the coat she brings is : ermine, three greyhounds courant sable, collared gules, on a canton of the last a lion passant or, in chief a crescent sable This coat (with the crescent to denote the second son of a man in his father' lifetime) is almost the same (only the red dog-collars in the Appleby Parva coat of arms are different) as that of the Moore who was Lord Mayor of London in 1682. His canton contains the same lion ("of England"), and is described as "for augmentation", which suggests an honour granted maybe for his position or his service in the rôle. Boutell makes the point that some augmentations were to distinguish one name-holder from un-related bearers of the same name, so our shield, by default, seems to make a relationship between this Lord Mayor of London and our Leicestershire Moores. Charles Townley, with an eye to the "Consideration", would have picked up on this.

Thus, a ROUGH Pedigree of the Townleys down to (Sir) Charles might look something like figure 10 below:

There is, of course, no ninth quarter for Charles Townley's wife Mary, because he wasn't married by the date of this drawing – and it's uncertain whether his wife was of an armigerent family. If there were a ninth coat, it would probably have necessitated the multi-shield's being divided into three rows of three (like the Disney window at Flintham Church, 04 above).

We have seen earlier that a herald in the years leading up to this period of history might not necessarily have been expected to be lily-white, actually in himself or in how he, even mistakenly, appeared to others, but it's interesting to conclude this glimpse into Charles Townley's work and attitudes by our being aware that the he was not highly rated by his contemporary heralds or later historians of the College of Arms, because of some monopolistic venality, and the aggressive nit-picking versified here by Henry Hill, 18th Century Windsor Herald:

"[Grose] had no great taste for Heraldry, but …

When captious Townley has the least pretence

To e'en the smallest share of common sense,

………………………………………………

Then Hawkes and Doves shall marriages contract"

Bibliography

Some recommendations for you about books I use, which you might like to look at:

"Heraldry in National Trust Houses" - Thomas Woodcock & John Martin Robinson - National Trust

"An Introduction to Heraldry" – Stefan Oliver – Chancellor Press

"The Illustrated Book of Heraldry" – Stephen Slater – Hermes House

[Grab one – often going cheap now – absolutely & readably super!]

"The Observer's Book of Heraldry" – Charles MacKinnon of Dunakin – Frederick Warne

[This book is a collector's item – hang onto this gold dust if you find one!]

"Heraldry: Its Origins and Meanings" – Michel Pastoureau – New Horizons Series, Thames & Hudson

"Heraldry: Sources, Symbols and Meaning" – Ottfried Neubecker (plus JP Brooke-Little) - Little, Brown & Company

These will all refer you to the Standard Works of Reference – Burke, Papworth, Fairbairn & Boutell

By all means look at our website, to see some musings on Heraldry – www.vicandchris.com

By Vic Taylor 2008

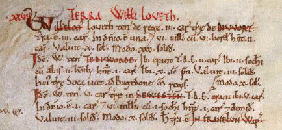

- Domesday

Diseworth appears in the Domesday Book, as an entry for one William Loveth:

LEICESTERSHIRE

XXVII. THE LAND OF WILLIAM LOVETH

WILLIAM Loveth holds of the king 3 carucates of land of DISEWORT. There is land for 3 ploughs. In demesne is 1 [plough]; and 6 villans with 6 bordars have 2 ploughs. It was worth 10s ; now 30s ;

The same William holds THEDDINGWORTH. TRE 2 ploughs were there. There 2 sokemen with 2 other men have 1 plough. There are 10 acres of meadow. It was worth 3s ; now 10s. The soke of this land belongs to the king's manor of Great Bowden.

The same William holds 5 carucates of land in SEWSTERN. TRE 5 ploughs were there. In demesne is 1 plough; and 6 villans with 1 sokeman have 1 ½ ploughs. It was worth 3s ; now 10s. This land is [in] "Stofalde" the third part of 1 virgate. +Waste.+ IN FRAMLAND WAPENTAKE.

The Domesday Book is a great land survey from 1086, commissioned by William the Conqueror to assess the extent of the land and resources being owned in England at the time, and the extent of the taxes he could raise. The information collected was recorded by hand in two huge books, in the space of around a year. William died before it was fully completed.

The Domesday Book provides extensive records of landholders, their tenants, the amount of land they owned, how many people occupied the land (villagers, smallholders, free men, slaves, etc.), the amounts of woodland, meadow, animals, fish and ploughs on the land (if there were any) and other resources, any buildings present (churches, castles, mills, salthouses, etc.), and the whole purpose of the survey - the value of the land and its assets, before the Norman Conquest, after it, and at the time of Domesday. Some entries also chronicle disputes over who held land, some mention customary dues that had to be paid to the king, and entries for major towns include records of traders and number of houses.

- Diseworth's Landscape

Although Diseworth is surrounded by motorways and an airport, there are clues to its past in the landscape. Ones of these is the presence of clear signs of the ancient field system known as ridge and furrow.

Ridge and furrow in fields on Long Mere Lane

Ridge and furrow in fields on Long Mere Lane

The term ridge and furrow is used to describe the pattern of peaks and troughs created in a field, caused by the system of ploughing used during the Middle Ages. Early examples date to the immediate post-Roman period and the method survived until the seventeenth century in some areas. The characteristic shape arises from the use of non-reversible ploughs on the same strip of land each year. Traditional ploughs turn the soil over in one direction, to the right. This means that the plough cannot return along the same furrow. Instead, ploughing is done in a clockwise direction around a long rectangular strip (a land). On reaching the end of the furrow, the plough is removed from the ground, moved across the unploughed headland (the short end of the strip), then put back in the ground to work back down the other long side of the strip.

The width of the ploughed strip is fairly narrow, to avoid having to drag the plough too far across the headland. This process has the effect of moving the soil in each half of the strip one furrow's-width towards the centre line. In the Middle Ages each strip was managed by one small family, within large common fields, and the location of the ploughing was the same each year. The movement of soil year after year gradually built the centre up of the strip into a ridge, leaving a dip, or "furrow" between each ridge (note that this use of "furrow" is different from that for the furrow left by each pass of the plough). The building up of a ridge was called filling or gathering. It is thought that the raised beds offered better drainage (on some well-drained soils the fields were left flat). The dip often marked the boundary between plots.

Although they varied, traditionally a strip would be a furlong (a "furrow-long") in length, (220 yards, about 200 metres), and a chain wide (22 yards, about 20 metres), giving an area of one acre (about 0.4 ha), or about a day's ploughing. Where ploughing continued over the centuries, later methods removed the ridge and furrow pattern. However, in some cases the land became grassland, and where this has not been ploughed since, the pattern has often been preserved. Surviving ridge and furrow may have a height difference of 18 to 24 inches (0.5 to 0.6 m) in places, and gives a strongly rippled effect to the landscape.

This is the case in the examples shown from the Diseworth area:

Fields to the north of the village (Grimes Gate on the right)

Fields to the north of the village (Grimes Gate on the right)

Fields to the left of Long Mere Lane (see pictures above)

Fields to the left of Long Mere Lane (see pictures above)

In this close up view of the fields, the extend of the ridge and furrow system is clear. The images shows the ridges to be straight, indicating they were worked relatively recently.(In early ridge and furrow, the tendency was for the path of the oxen and plough to cause a twist at the end of each furrow slightly to the left, making these earlier ridge and furrows a slight reverse-S shape).

- Thatching

A short history of thatching

The art of thatching with natural plant materials has been known in this country since time immemorial. The use of thatch for roofing emerged from the Bronze Age with thatched cottages and farm buildings becoming the norm in rural Britain for over a millennium. It was common practice in those days for buildings to use lightweight, irregular materials, such as wattle and daub walls, and cruck beams. These structures could not take the weight of any heavier roofing material other than thatch. People would only be able to use what they could source locally: this meant materials as varied as broom, sedge, flax, grass, and straw were commonly used.

Every period since the Romans has constructed buildings with thatched roofs, and examples still exist with at least part of the base thatch dating from medieval times, when many of the thatching techniques still in use today were already standard practice. They are one of the most characteristic sights in our countryside, but they are practical too – they are warm in Winter and cool in Summer, but in addition, a thatched roof offers superior sound insulation properties, which is a real benefit in Diseworth !